Healthcare Access for Undocumented Immigrants

Due to their legal status, undocumented immigrants face many barriers to receiving adequate healthcare

Research Shows

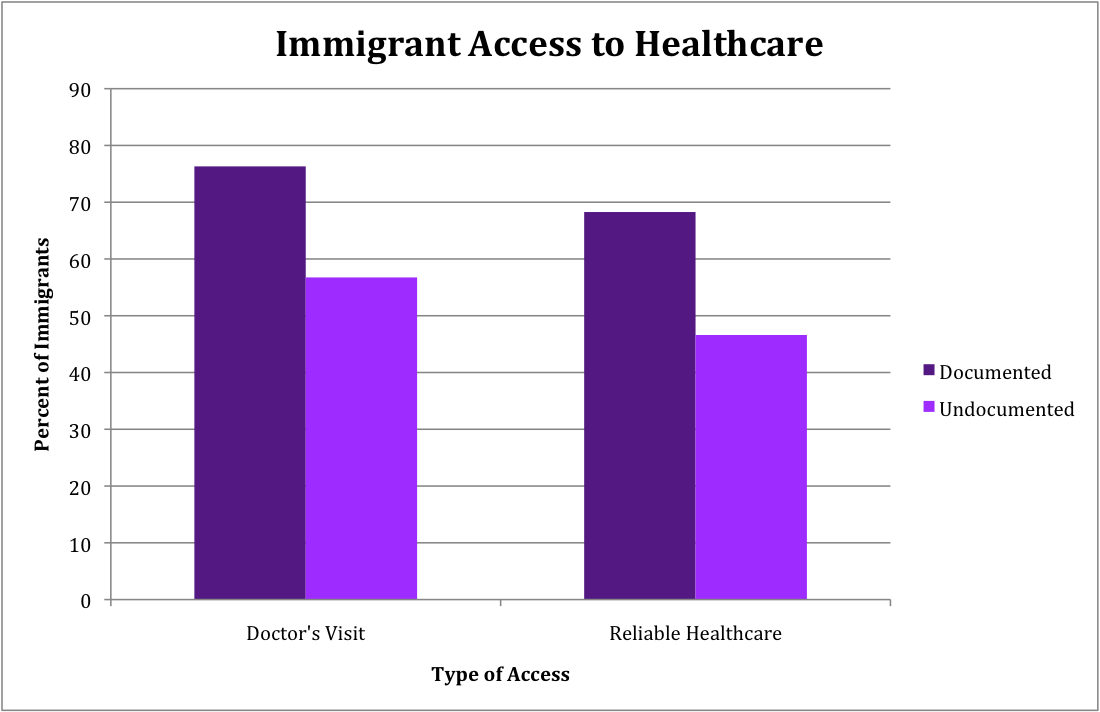

A study of undocumented Mexican immigrants in California found that only 52% had a usual place to seek healthcare, although 60% reported visiting a doctor in the last year (2). “Safety-net providers,” such as Federally Qualified Health Centers (FQHCs), community centers or migrant health clinics provide most care to undocumented migrants, rather than traditional healthcare providers (3). Undocumented immigrants are not eligible for coverage under the Affordable Care Act (ACA), even if they are “lawfully present” under Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) (4). In fact, scholars expect the ACA will reduce access for undocumented immigrants. As uninsured rates for citizens and legal residents drop, fewer places may serve the uninsured, leaving undocumented immigrants with fewer options to receive care (5). Barriers to care for undocumented immigrants also affect their families, as citizen children of undocumented immigrants are less likely to receive regular care than children of U.S.-born parents (4). Tensions arise from healthcare providers’ ethical commitments to offer care to all people who need it, particularly in emergencies, and judgments about who should pay for healthcare. Undocumented status sharpens divisions in related policy debates.

Intended Audience

- Healthcare officials

- Community leaders

- Advocates

- Policymakers

Related Projects

Research Details

Because data on undocumented immigrants is limited, quantitative studies that separate undocumented immigrants from those with other legal statuses rely on estimates of undocumented immigrants in their samples. The methods scholars used to estimate the population depend on available data (2;6;7). Two quantitative studies cited here used the California Health Interview Survey, and two others relied on the national Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (2;6;7;8). Other sources include three opinion essays (1;3;5), two studies based on qualitative surveys (4;9), and one quantitative study on Mexican-origin migrants in rural Oregon (10).

Continuing Debates

Healthcare provision for undocumented immigrants remains politically controversial (3). While public opinion is divided about the desirability of offering healthcare to undocumented immigrants, public health scholars agree that expanded healthcare access for this population benefits undocumented immigrants and all of U.S. society. They offer many specific reasons why expanding healthcare access makes good sense, ranging from economic benefits, public health concerns about immigrants spreading disease, and protection of elderly immigrants and children (11). Multiple studies show that undocumented immigrants utilize healthcare services less than documented residents or citizens (6;7;8).

Implications

Policy change at the federal level could increase access for all undocumented immigrants; local communities can also increase access to healthcare for some of this population. Undocumented immigrants need more information about how the ACA affects them, especially those living in mixed-status families (4). The development of trust between undocumented immigrants and service providers such as FQHCs can increase utilization of existing services (4;10).

Potential Challenges

- Many rural areas are already medically underserved, which shapes some citizens’ opinions that undocumented immigrants unnecessarily strain the local health care system (9).

- As the ACA reduces the number of uninsured people, resources to serve the uninsured, which are a key source of care for undocumented immigrants, may begin to disappear (1).

- Providing care requires attention to transportation problems, language barriers, misconceptions, and other difficulties that prevent some undocumented immigrants from accessing existing care options (4).

Sources and Further Reading

- Sommers, Benjamin D. 2013. “Stuck between Health and Immigration Reform – Care for Undocumented Immigrants.” The New England Journal of Medicine 369 (August): 593-595. Accessed June 15, 2015. http://dx.doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp1306636

2. Bustamante, Arturo Vargas, Olivia Carter-Pokras, Hai Fang, Jeremiah Garza, Alexander N. Ortega, John A. Rizzo, and Steven P. Wallace. 2010. “Variations in Healthcare Access and Utilization Among Mexican Immigrants: The Role of Documentation Status.” Journal of Immigrant Minority Health 14, no. 1 (October): 146-155. Accessed June 15, 2015. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10903-010-9406-9

3. Galarneau, Charlene. 2011. “Still Missing: Undocumented Immigrants in Health Care Reform.” Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved 22, no. 2 (May): 422-428. Accessed June 15, 2015. PAIS International.

4. Castañeda, Heide, and Milena Andrea Melo. 2014. “Health Care Access for Latino Mixed-Status Families: Barriers, Strategies, and Implications for Reform.” American Behavioral Scientist 58, no. 4 (December): 1892-1909. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0002764214550290

5. Breen, James O. 2012. “Lost in Translation–Cómo se dice, ‘Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act’?” The New England Journal of Medicine 366, no. 22 (May): 2045-2047. Accessed June 25, 2015. http://dx.doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp1202039

6. Pourat, Nadereh, Steven P. Wallace, Max W. Hadler, and Ninez Ponce. 2014. “Assessing Health Care Services Used By California’s Undocumented Immigrant Population In 2010.” Health Affairs 33, no. 5 (May): 840-847. Accessed June 25, 2015. http://dx.doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2013.0615

7. Stimpson, Jim P., Fernando A. Wilson and Dejun Su. 2013. “Unauthorized Immigrants Spend Less Than Other Immigrants And US Natives On Health Care.” Health Affairs 32, no.7 (July): 1313-1318. Accessed June 25, 2015. http://dx.doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2013.0113

8. Stimpson, Jim P., Fernando Wilson, Karl Eschbach. 2010. “Trends in Health Care Spending For Immigrants In The United States.” Health Affairs 29, no. 3 (February): 544-550. Accessed June 25, 2015. http://dx.doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2009.0400

9. Marrow, Helen B. 2012. “Deserving to a point: Unauthorized immigrants in San Francisco’s universal access healthcare model.” Social Science & Medicine, 74, no. 6 (March): 846-854. Accessed June 25, 2015. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.08.001

10. López-Cevallos, Daniel F., Junghee Lee, and William Donlan. 2014. “Fear of Deportation is not Associated with Medical or Dental Care Use Among Mexican-Origin Farmworkers Served by a Federally-Qualified Health Center–Faith-Based Partnership: An Exploratory Study.” Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health, 16, no. 4 (August): 706-711. Accessed June 25, 2015. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10903-013-9845-1

11. Viladrich, Anahí. 2012. “Beyond welfare reform: Reframing undocumented immigrants’ entitlement to health care in the United States, a critical review.” Social Science & Medicine, 74, no. 6 (March): 822-829. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.05.050

Author(s)

Alyssa Berg and Emma Youngquist