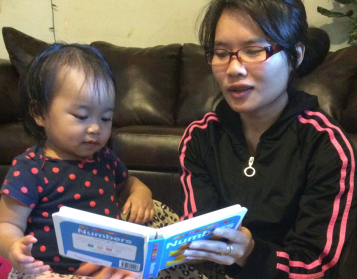

Refugee Health Connections (RHC): a home visit program supporting family well-being

Provides home visits and health sessions to promote healthy outcomes in the South East Asian Community.Participants

- Designed to serve Southeast Asian Refugees, currently serving mostly Karen and Burmese speaking families.

Desired Outcomes

- Link refugees to health care services to support and educate.

- Create a safe space that familiarizes refugees to professionals in fields such as health care, law enforcement, or education.

- Meet refugees needs, such as transportation and interpretation services.

- First listen to refugees to know their needs.

How this project/organization build relationships

RHC builds trust within the community when refugees familiarize themselves with nurses and police officers who use the RHC conference room for educational events. By listening to the refugee community first, RHC becomes considerate and sensitive to refugee families’ needs.

Costs

- Interpreter(s) who speaks Burmese and Karen

Time resources

- Advisory committee meets monthly, composed of community partners

- Presentations from the Marshalltown Police Department

- Medical professionals visited refugee homes to better understand their experiences and get to know them better

- Invite refugees to teach about what the culture is like

Other resources

- Familiarity with grant funding sources and opportunity.

- Interpreting staff provides transportation to healthcare services when available for free.

Direct Partners

- Church elders and pastors from local SE Asian Refugee congregations

- Medical and health professionals: Primary Health Clinic, local hospital, and Substance Abuse Treatment Unit of Central Iowa (SATUCI), McFarland Clinic

Sponsors

- Local level grant

- Funded by a $200,000 start-up grant received by Child Abuse Prevention Services (from the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) under grant number D04RH28398, Rural Health Care Services Outreach Grant Program)

- Used during 2015-2018

- After the funding expired, they used decategorization funding:

- Decategorization funding for two years from the Department of Human Services ($8000)

Our Story: "There is no one who is doing a program like [the RHC]."

The Refugee Health Connections (RHC) program is a culturally competent home visit program that provides resources and information about child-rearing and family well-being to Burmese and Karen refugees situated in Marshalltown, Iowa. RHC is part of Child Abuse Prevention Services’ (CAPS), a non-profit organization that alleviates the factors causing child abuse. CAPS keeps children out of the foster system by keeping at-risk families safe. They have several programs, such as the Latino-focused Strong Foundations (SF) home visit program. Before RHC, the Building Healthy Families program existed, but that program served the general population instead of only refugees. CAPS now has Building Healthy Families, SF, and RHC as their family support programs addressing the needs of the community.

The RHC program began by making use of existing networks established by CAPS or referrals by well-connected individuals. Hiring staff who speak a refugee’s native language aligns with RHC’s community health worker model. RHC gauges what newcomer clients need and then facilitates or provides those needs to ensure child and family well-being. During a meeting with the refugee community in a church, RHC sought to know the needs of the community. By first initiating contact through church elders and pastors, RHC introduced itself in a nonthreatening manner to the refugees. RHC decided to build trust with the refugee community through the church because in Marshalltown the majority of Burmese refugees are Christians, then Buddhists.

RHC sees breaking down language barriers as an essential part of realizing family well-being. During the first year, RHC hired three female interpreters who conducted culturally grounded home visits. They spoke a total of five languages: Burmese, Karen, Chin, Karenni, and Thai. Esmeralda Monroy, the Program Manager, mentions that their interpreter hiring process was not dictated by education, but rather by the potential to make connections with other community members. She says that it amazes other people when she tells them that the key to building trust with refugees is to break down the language barrier. All of the original interpreting staff quit either because they moved out of state or because they wanted to stay at home after having a child. Now RHC has one interpreter who only speaks Karen and Burmese. Although it is not in the job description, the interpreter is sometimes summoned by the Marshalltown Police Department for instances where the police cannot communicate with a resident. Budget cuts meant that they could not hire more staff, according to Program Director Nikki Hartwig who does all the grant writing for RHC. As a result, RHC now mainly serves Karen and Burmese refugees. The staff is under enormous pressure after they lost interpreters. Monroy emphasizes, “[RHC began] successfully because of the three [interpreters], hands down.”

[RHC began] successfully because of the three [interpreters], hands down.

“House visitations [began] by educating ourselves,” says Monroy. Once RHC began home visits with refugees, they noticed an unexpected dental need and a significant amount of moms with gestational diabetes, issues that would have gone unnoticed by RHC, if not for the home visitation program. Both Hartwig and Monroy apply an adaptable structure to the RHC program in order to readily respond to the needs of the refugee community. “We’re flexible, change things to meet the needs of [the refugee] families,” states Monroy. In a continual effort to attain cultural competency, RHC has previously invited a refugee to teach about their respective culture. As long as the children and everyone else at home are safe, then RHC staff conducting home visits do not tell refugees what to do.

The RHC program provides a familiar environment and a common location for refugees. RHC sometimes hosts meetings between refugees and the police department. On one occasion, the police and sheriff department tailored their presentation to address the fears within the refugee community. RHC also had other community partners use the space to interact with the refugees. A registered nurse has taught on health topics such as dental care, HIV, AIDS, Hepatitis B. “Those partners started with a phone call,” says Monroy. In the same building where RHC is located, refugees can get baby items at the Nest store. By making the space a one-stop shop, people are invited to go to the RHC, meet new faces, and build connections.

Benefits

- FY2019: served 35 families with 52 children in total; completed 656 home visits

- RHC links families and healthcare providers because its staff provides transportation, interpretation, educational, and informational resources. RHC minimizes the number of places refugees travel for services as they have the Nest, a store that sells baby items, in the same building.

- RHC keeps children out of the state’s protective services.

Challenges

- Decreasing the waiting list of individuals who want to receive the RHC services.

- RHC worries about the uncertainty in keeping their funding. Interpreters are understaffed when compared to the need to expand beyond two languages. RHC could help some refugees after it lost funding, so it referred the families to other programs within CAPS or to MICA, but at the risk of not having their needs fully met.

- Keeping up with a changing demographic is difficult, especially when the U.S. government is closing the window on Southeast newcomers. Marshalltown received many different migrant groups: first Hispanic, then refugees from Southeast Asia, now Congolese refugees.

Things to Remember

- Tailor services to fit client’s needs because families have different experiences and needs.

- Self-educate first about cultural and ideological differences before making goals.

- Assemble a flexible and adaptable staff